INTERNALIZED HOMOPHOBIA

You were just recently told by a friend to “deal with your internalized homophobia.”

You force your partner to stay in the closet with you.

You feel contempt or disgust towards LGBTQ people who don’t “blend in.”

You can’t come out, even in safe communities and settings.

You’ve tried to change your sexual orientation through conversion therapy, prayer, or medical treatment.

You cannot have emotionally intimate or romantic relationships, even though you desire it.

You think about committing suicide because of your sexuality.

These are just a few of the many signs of internalized homophobia, an issue that affects the vast majority of LGBQ individuals and belongs at the forefront of the fight for justice and equality. Working to overcome it can lead to immensely positive results such as emotional and physical well being, a stronger more effective political movement, and a more compassionate world.

_______________________________________

CONTENTS

The definition

Problems with the term

Why does it happen?

What does internalized homophobia look like and how do I know if I suffer from it?

Secrecy, dishonesty, problems coming out, horizontal oppression, mental and physical health issues, problems with intimacy

Negative impacts

Why are we all impacted so differently?

Overcoming internalized homophobia

References / notes

Further Reading

_______________________________________

THE DEFINITION

Simply put, internalized homophobia happens when LGBQ individuals are subjected to society’s negative perceptions, intolerance and stigmas towards LGBQ people, and as a result, turn those ideas inward believing they are true.

It has been defined as ‘the gay person’s direction of negative social attitudes toward the self, leading to a devaluation of the self and resultant internal conflicts and poor self-regard.’ (Meyer and Dean, 1998).

Or as “the self-hatred that occurs as a result of being a socially stigmatized person.” (Locke, 1998).

PROBLEMS WITH THE TERM

Many LGBQ people do not relate to the expression “internalized homophobia” and as a result end up rejecting the idea before thoroughly examining its meaning. The word “internalized” presents the first barrier. “The concept suggests weakness rather than the resilience demonstrated by lesbians and gay men and keeps the focus away from the structures of inequality and oppression.” (Williamson, I., 2000) The word “homophobia” is the next complication – a difficult and seemingly illogical possibility. How can someone who identifies as LGBQ also have feelings of dislike, fear, and disgust towards themselves? So what can we do about the fact that the combination of words “internalized” and “homophobia” feel unrelatable for so many LGBQs?

Researchers have suggested that using ‘heterosexism’, ‘self-prejudice,’ and ‘homonegativity,’ in addition to the widely accepted term “internalized homophobia,” can help to add depth to our comprehension of the true meaning of the issue.

WHY DOES IT HAPPEN?

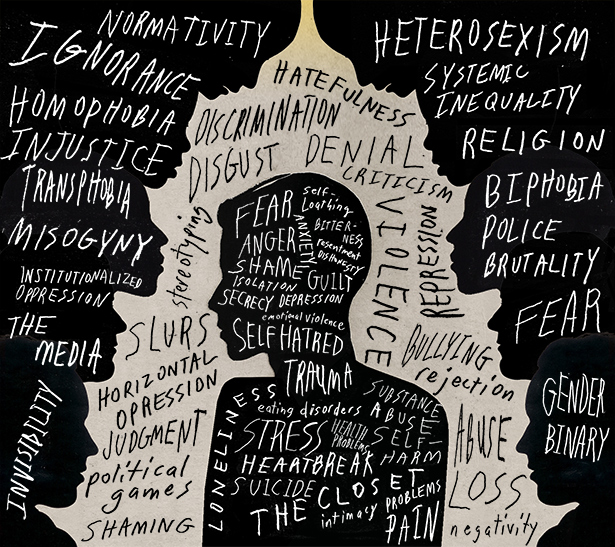

Internalized homophobia is a concept much more nuanced than it’s simple definition would suggest. It is clear that the word “homophobia” in this context, is misleading – the over simplified idea that it is individual acts of fear and ignorance diverts our attention from the much more pervasive systemic oppression that is at the root of the problem. The hateful and intolerant behavior of those closest to us often has the most profound impact (parents, church community, peers, partners). While they should be held responsible as individuals, the real culprit is an aggressively heterosexist society that is defining what is “normal,” and therefore what is “right” and “wrong,” through laws, policy, culture, education, health care, religion and family life. This systemic oppression is meant to enforce the gender binary, marginalize LGBTQ people, and keep heterosexual people and their relationships in a position of dominance and privilege.

When we see that homophobia is a result of a this larger system, we see that it is institutional; that it is impossible to exist outside of it; that the real definition of it is so much more than the dictionary simplicity of “irrational fear of, aversion to, or discrimination against homosexuality or homosexuals;” that the root structure is vast, affecting every aspect of life and culture. All of these factors make dismantling heterosexism extremely complicated, and uprooting internalized homophobia even more so.

WHAT DOES INTERNALIZED HOMOPHOBIA LOOK LIKE?

HOW DO I KNOW IF I SUFFER FROM IT?

A few scales have been developed by psychiatrists and researchers to measure internalized homophobia such Ross and Rosser’s “Four Dimensions.” This includes the examination of four key areas of a person’s LGBQ identity: public identification as being gay, perception of stigma associated with being gay, degree of social comfort with other gays and beliefs regarding the religious or moral acceptability of homosexuality. Another example is the IHP scale, developed by psychiatrists Meyer and and Dean, which includes a long list of questions designed to be self-administered. While these scales might be useful on a preliminal level, we must also consider the issue well beyond the categories set forth by the psychological establishment and remember that the question of whether or not you suffer from internalized homophobia is one that is best answered by yourself. The manifestation of internalized homophobia, as well as the extent to which LGBQ people suffer from it, is as varied and layered as our identities, which makes recognizing it a complicated process. Below we do our best to explore many possible expressions and outcomes of internalized homophobia.

Secrecy / Dishonesty

‘The awareness of stigma that surrounds homosexuality leads the experience to become an extremely negative one; shame and secrecy, silence and self-awareness, a strong sense of differentness – and of peculiarity – pervades the consciousness.’ (Plumer,1996). The role of secrecy and dishonesty in cases of internalized homophobia, is significant. Some examples include:

- Denial – ranging from aggressive and hateful behavior to denying yourself the life and love you desire;

- Lying to yourself about attraction and sexuality;

- The inability to “come out” if you want to, and if you can safely. (see more about “coming out below);

- Being selectively “out” (see “coming out” below);

- Secret relationships;

- Forcing others to keep secrets or remain in the closet;

- Lying by omission

The emotional havoc that secrecy and dishonesty can create for an individual varies. While burdened with the symptoms of internalized homophobia it is difficult to have a clear perspective of the harm we do to ourselves. This is why it’s often due to an accusation of a loved one that we are compelled to explore the concept in the first place.

Horizontal Oppression

Also known as horizontal hostility or lateral violence, horizontal oppression is one of the most damaging results of internalized homophobia. It functions as a cycle of abuse, and happens when an LGBQ person, subjected to homophobia / biphobia / heteronormativity, begins to discriminate against other LGBQ people, thereby colluding with and perpetuation heterosexism. Horizontal oppression can be found amongst women (horizontal misogyny) and amongst people of the same racial group (horizontal racism), and in just about every type of oppressed minority group. It destabilizes movements for justice and equality, and keeps us fighting amongst ourselves rather than focusing on the big picture issue of institutionalized oppression.

Horizontal oppression can manifest as anything from:

- Deeply closeted politicians, religious leaders and “powerful” people who advocate and lobby against the LGBTQ community

- Feeling disgust towards other LGBTQ people who don’t express themselves in a heteronormative way

- Excessive judgment of other LGBTQ people

- Anger and resentment toward other LGBQ people for being out, or proud of their identity

- Transphobia, gender policing, shaming or harming LGBTQ individuals who do not fit into the gender binary

- Anger or embarrassment that other LGBTQ people “represent” you

- Believing that the movement for justice is a single-issue endeavor (usually marriage equality), and failing to remember that LGBQ people come from every type of background, often facing multiple, interconnected forms of oppression such as racism, cisgenderism, ableism, classism, sexism, etc.

To combat horizontal oppression we must:

- Respect the diversity of the LGBTQ community

- Remember that outspoken, visible LGBTQ people have been at the forefront of the LGBTQ rights movement from the very beginning, and continue to face the most violence, and discrimination

- Credit visibility as one of the key factors in the progress of the LGBTQ equality movement

- See that policing the gender expression of LGBTQ individuals is a form of transphobia and heteronormative violence.

- Be aware of the ways that we collude with heterosexism and therefore harm LGBQ people

Problems with Coming Out

In Beyond the Closet; The Transformation of Gay and Lesbian Life, being in the closet is described as a “life-shaping pattern of concealment.” Being closeted is linked with high-anxiety, low self-esteem, increased risk for suicide and general lack of fulfillment. Much of the LGBQ discussion about honesty centers on coming out. While it’s not an internalized homophobia cure-all, it is more often than not, a step forward, and can be an incredibly empowering act for most LGBQ people. It relieves the pressure of having to live a life of secrecy; it is an act of self-love and recognition.

But coming out can also be dangerous. Being honest about your LGBQ identity can result in violence, rejection, loss of home, loss of employment. We unequivocally advocate for an approach that minimizes harm to the person coming out. The key is to recognize the truth of what kind of harm you’re facing and weigh the balance of your emotional and physical safety with your emotional and physical needs. What is more damaging – to face the disapproval of a parent, or to lose your partner? To lose your home or manage the stress of leading a double life?

When a person expresses fear or reluctance about coming out, many “out” LGBQ people have strong reactions, judgments, and painful memories. George Chauncey, professor of history and author of Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture and the making of the Gay Male World, discusses ‘the image of the closet’ and the judgment heaped on those who would not, or could not come out of it.

“Before Stonewall (let alone World War II), it is often said, gay people lived in a closet that kept them isolated, invisible, and vulnerable to anti-gay ideology. While it is hard to imagine the closet as anything other than a prison, we often blame people in the past for not having had the courage to break out of it . . . , or we condescendingly assume they had internalized the prevalent hatred of homosexuality and thought they deserved to be there. Even at our most charitable, we often imagine that people in the closet kept their gayness hidden not only from hostile straight people, but from other gay people as well, and, possibly, from themselves.”

Many critics of the you-must-come-out-of-the-closet doctrine argue that not only does it diminish the worth of the LGBQ lives from the past when it was not safe to be out, but overtime it has homogenized the LGBQ timeline into a 3 step process (in the closet, preparation to come out, out), and, as philosopher and gender theorist Judith Butler argues in Imitation and Gender Insubordination, the in/out metaphor creates an over-simplified binary: in = dark, regressive, marginal, false; out = illuminating, freeing, true.

We know that things are never as simple as that, and shaming those who remain in the closet is a mutation of heterosexist oppression. Also, as many studies have shown, internalized homophobia may never be completely overcome, and therefore may continue to affect LGBQ individuals long after “coming out.” It is true that coming out to important people in your life may indicate that you’ve overcome personal shame and self-devaluation associated with being LGBQ. But, a lack of outness should not be taken to indicate the opposite and therefore should not be seen as the primary symptom of internalized homophobia (Eliason & Schope, 2007).

Mental and Physical Health Issues

Depression / Anxiety / Self Esteem Issues / Self-harm / Suicide / Substance Abuse / Eating Disorders

Chronic stress has extremely negative consequences for the human body, such as, but certainly not limited to, sleeplessness, depression, anxiety disorders, increased susceptibility to illness, heart disease, and high blood pressure. LGBQ people, and in general, any minority or oppressed group, are likely to suffer additionally from what’s known as “minority stress,” a direct cause of internalized homophobia. “Minority stress,” arises from specific, negative events in a person’s life, as well as the whole of the minority person’s experience in the dominant, oppressive society. So, everything from fearing a family member’s judgment, to hearing homophobic slurs at school, to being the victim of a hate crime, to pressure to come out of the closet, to not being able to get married (and therefore claim access to the over 1,000 legal protections and benefits that come with marriage licenses) can contribute to “minority stress.”

As a result of this immense and insidious stress, many LGBQ people develop more serious health problems, and often (due to internalized homophobia) do not seek (or, due to homophobia, are not provided with) the medical attention they need. And so the self-perpetuating cycle of suffering continues.

Many academic and medical studies have linked the existence of internalized homophobia to other health issues and behaviors meant to punish or control the physical body, such as suicide, excessively risky sexual behavior, substance abuse and eating disorders, particularly in those who are lacking the proper support structures, community, and coping mechanisms. It is more difficult still to quantify the unconscious effects of internalized homophobia, especially within those who reject the possibility of it. But while we wait for more studies and analysis from the medical communities, it is imperative that we shine a light on this issue, which is harming so many LGBQ people, and injuring even more around us.

Inability to have intimacy, emotionally or physically

Internalized homophobia is directly connected to many negative outcomes in both romantic and non-romantic relationships. Examples can include, but are in no way limited to:

- Low self-esteem / negative self-view that can lead to avoiding substantial relationships or others avoiding you

- Dishonesty, which can prevent or destroy trust between friends and family

- Secrecy, which contributes to anxiety and a lack of self-worth, which can then be internalized by partners and friends

- Horizontal oppression (see section above on this topic)

- Perpetual lack of satisfaction from emotional and/or physical intimacy

- Verbal or physical abuse within friendships and romantic relationships

- Deep shame about sexual experiences

- Ambivalence, loneliness, isolation

- Inability to have emotionally intimate sexual encounters

- Preventing yourself from having sex even if you desire it

At the core of the prevailing stigma surrounding being LGBQ are unsubstantiated notions that LGBQ people are not capable of intimacy and maintaining lasting and healthy relationships (Meyer & Dean, 1998). The anxiety, shame, and devaluation of LGBQ people that is inherent to internalized homophobia is likely to be most overtly manifested in interpersonal relationships with other LGBQ individuals, creating intimacy-related problems in many forms. Empirical evidence supports these theoretical claims. With regard to romantic relationships, psychiatrists Meyer and Dean showed in a study that gay men with higher levels of internalized homophobia were less likely to be in intimate relationships, and when they were in relationships, they were more likely to report problems with their partners than gay men with lower levels of internalized homophobia. Similarly, in Ross and Rosser (1996) conducted a study showing that among gay and bisexual men, internalized homophobia was negatively associated with relationship quality and the length of individuals’ longest relationships. There are endless stories about love lost and relationships of all forms destroyed over the issue of internalized homophobia. For more reading on the topic, check out the references section of this article.

THE NEGATIVE IMPACTS OF INTERNALIZED HOMOPHOBIA

On the self

Internalized homophobia can prevent us from leading fulfilling lives. It can keep us in a place of perpetual shame, stress and anxiety. It can keep us from having close relationships with people, or ruin the relationships we do have. It can lead us down a path of bitterness, anger, and loneliness. It can prevent us from coming out of the closet and allowing ourselves the opportunity to be seen and loved for who we are. It can prevent us from ever experiencing love with another person. It can contribute to long-term illness, mental health problems, substance abuse and self-harm.

On others

Internalized homophobia, when left unchecked or unexamined can harm people around the suffering individual. It can lead to judgmental and hurtful outbursts. It can break trust between friends and family. It can cause years of heartbreak and struggle within romantic relationships, it can lead people in positions of power to make decisions that harm other LGBTQ people on a large scale. It can provoke shame, anxiety and stress, and impact the health of others.

On the movement

When left to unconsciously dominate a person’s psyche, internalized homophobia can perpetuate violence, intolerance and discrimination. Most significantly, it takes the focus away from the true culprit, the main source of pain and struggle – which is heterosexism, enforced heteronormativity, homophobia, biphobia and transphobia – by keeping us shortsighted and fighting amongst ourselves.

WHY ARE WE ALL IMPACTED SO DIFFERENTLY?

Despite the few common experiences that LGBQ people share, we are a group that reflects the diversity of all human beings on this earth. And every detail of a life, large or small can affect the way that internalized homophobia takes hold. For example, studies have shown that those who realize early in life that they are LGBQ are often more prone to serious internalized homophobia; they do not typically have the support of a community or access to information about their identities to properly shield themselves from parental ignorance or a homophobic society. By contrast, it is common for people living in regions with LGBQ equality to experience very little internalized homophobia if, unaware of their sexuality in youth, they realize they are LGBQ in adulthood.

Internalized homophobia is impacted by every aspect of identity, such as religion, race, class, geography, gender identity, family, friends, partners, as well all of the prejudices we carry. Additionally, many LGBQ people experience intersecting oppression, such as racism, transphobia, misogyny, and abelism, and thus are also vulnerable to multiple forms of internalized oppression.

While it would be impossible to describe everyone’s experience, recognizing commonalities, asking questions, and considering the feedback of our peers is an important step in getting a clearer picture of ourselves. An inevitable problem of a people so long repressed into invisibility is lack of representation, and due to this, internalize homophobia has an even greater ability to take hold in a person’s psyche.

HOW CAN IT BE OVERCOME?

Think critically about how internalized homophobia could be impacting your life, rather than rejecting the notion outright.

Read more about internalized homophobia. While this topic has less written about it than say, coming out, there is still a lot of information out there, especially moving personal accounts.

Community – building a support network is absolutely essential. The compassion of other LGBQ people and straight allies can be tremendously healing. Others who are at a different stage in the process can often offer valuable insight and solidarity.

Learn about the history of the LGBTQ rights movement. Find role models in the struggle. See all of the different identities and human beings it took to effect progress towards equality and justice.

Find an LGBTQ positive therapist, counselor or psychologist who can guide you through the reparative process.

Get away from toxic influences. This one can often be the most difficult. Typically, toxic influences include major players in our lives, such as family, religion, and friends.

If your religion is not accepting, consider leaving the church even for a time, or find a new church. If you refuse to leave, educate yourself. Refine your arguments. Learn about whether or not your religion truly teaches the immorality of gays, or if it is the interpretation of your religious leader. However, if your religious doctrine is perpetually in conflict with your identity, you may find the commitment more damaging than rewarding.

Clarify your perspectives by talking to friends and allies. Heterosexism and fear can skew our idea of the threats we truly face. For example, a person with an open-minded family, LGBTQ friends and enlightened teachers might still be overcome by crippling fear and internalized homophobia. Work to determine where you stand.

Practice self-awareness. Be aware of your negative reactions, critical self-talk and judgment of other. Each time you do it, examine the source.

If you can do it safely, come out of the closet. While it has potential to be painful, and most certainly will be repetitive and exhausting, this step can be immensely rewarding.

Try to overcome your fear of rejection.

Remember that internalized homophobia is not coming from inside of you. You are not sick, and you don’t need to be cured. It was forced upon you, in a suffocating and violent way by a homophobic society. If you have been accused of having it, or if you wonder about yourself, don’t feel guilty or shameful, just take the steps, one by one, to free yourself of this weight that keeps us all down.

NOTES / REFERENCES

This article aimed to explore the meaning, causes and symptoms of internalized homophobia, and propose practical solutions to overcome it. Our information is based on many articles, studies, papers and personal accounts, but every LGBQ person has their own unique story, which results in the symptoms of internalized homophobia being varied and layered. Revel & Riot is not a medical or mental health organization, so please use our article as a reference, in addition to other forms of support.

In the article we use the acronym LGBQ most of the time, and sometimes use LGBTQ when referring to the general community and movement. While recognizing the fluidity and intersectionality of sexuality and gender, it is important to distinguish that internalized homophobia and internalized transphobia are not the same thing.

Barnes, David M. and Ilan Meyer. (2012). Religious Affiliation, Internalized Homophobia, and Mental Health in Lesbians, Gay Men, and Bisexuals. Am J Orthopsychiatry.

Butler, Judith, (1990). Imitation and Gender Insubordination. Inside Out: Lesbian Theories, Gay Theories.

Chauncey, George, (1995). Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture and the making of the Gay Male World 1890-1940.

Davies, D., (1996). Homophobia and Heterosexism, in Pink Therapy.

Eliason MJ, Schope R. Shifting sands or solid foundations? Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender identity formation in The health of sexual minorities: Public health perspectives on lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender health.

Frost, David M., and Ilan Meyer. (2009). Internalized Homophobia and Relationship Quality Among Lesbians, Gay Men and Bisexuals, Journal of Counseling Psychology.

Gonsiorek JC. Mental health issues of gay and lesbian adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health Care.

Herek, Gregory M., Jeanine C. Cogan, J. Roy Gillis. (2009). Internalized Stigma Among Sexual Minority Adults: Insights From a Social Psychological Perspective, Journal of Counseling Psychology.

Lock, James (1998). Treatment of Homophobia in a Gay Male Adolescent, American Journal of Psychotherapy.

Meyer IM, Schwartz S, Frost DM. (2008) Social patterning of stress and coping: Does disadvantaged social status confer more stress and fewer coping resources? Social Science & Medicine.

Meyer IH, Dean L. (1998) Internalized homophobia, intimacy, and sexual behavior among gay and bisexual men, in Stigma and sexual orientation: Understanding prejudice against lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals.

Meyer IH. (2003) Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence, Psychological Bulletin.

Ross MW, Rosser BRS. (1996) Measurement and correlates of internalized homophobia: A factor analytic study. Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Plummer, K. (1995). Telling Sexual Stories.

Pouiln-Deltour, William J. (2008). France’s Gais Retraites: Questioning the ‘Image of the Closet,’ Modern and Contemporary France.

Siedman, Steven, (2003) Beyond the Closet; The Transformation of Gay and Lesbian Life.

Williamson, Iain R. (2000). Internalized Homophobia and Health Issues Affecting Lesbians and Gay Men, Oxford University Press.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/laverne-cox/hung-up-on-our-bullies-in_b_1079271.html

http://www.healthyplace.com/gender/gay/internalized-homophobia-homophobia-within/#story

http://www.bilerico.com/2010/05/letting_go_of_internalized_homophobia.php

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/news/internalized-homophobia/

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/levi-kreis/from-selfloathing-to-self_b_1180269.html

http://www.dallasvoice.com/internalized-homophobia-snakes-lgbt-community-10164698.html

http://everydayfeminism.com/2013/08/put-out-internalized-racism/

http://everydayfeminism.com/2015/03/truth-of-coming-out/